1542. Fuchs and The Most Beautiful Herbal Ever Written.

The Most Beautiful Herbal Ever Written.

Introducing Leonard Fuchs' herbal of 1542; the Historia Stirpum. In this magnificent and ground-breaking book, Fuchs produced what was clearly a labour of love in the form of the most beautifully and accurately illustrated herbal ever produced.

What made his herbal so outstanding was that each picture in his herbal was from an original woodcut based on the actual living plant. While today we would not expect illustrations to be based on anything else, in Fuchs’ time, this represented an incredibly unique effort and a marked break with tradition. Such was indeed his intention. In not allowing his craftsmen to ‘indulge their whims’, he desired to produce a book which would genuinely help people to identify the plants described. In many ways, his success in this is notable in that this was primarily a picture guide book to plants. The descriptions of the herbs and their uses was still based largely on classical sources,particularly Dioscorides, but annotated where possible with Fuchs’ own knowledge, though in practice this meant plants which grew near to where he lived in Germany.

Nevertheless, Fuchs’ book was a game changer. No one now could realistically produce books which did not properly illustrate the plants they were describing; at least not if they wished to be taken seriously. Renaissance botany would rest upon this work as its reference point. In practice, sadly, this meant that many subsequent books would simply copy Fuchs’ prints and reproduce them in their own pages. Even that though was an improvement to the dire state botanical illustration had sunk to for the last thousand years. Even more unusually, Fuchs actually gave credit to the artists involved in illustrating the work. Given that the absolute norm was to copy and copy and copy, this was so radical one wonders how it was perceived at the time. Fuchs must have been supremely confident in his belief in the value of his new herbal to have so clearly emphasised its contemporary nature, rather than relying on ‘ancient authority’ as was the more typical fashion.

Of Arum, Fuch says:

“Later physicians tell us the aron has the property of dispersing, reducing, and cleansing; therefore it heals swellings of the ears, piles, strumas and hard tumors, removes deformities of the face and skin. Lastly, they write that its root, reduced to a powder, diminishes the overgrowth of flesh in wounds. The very extreme bitterness to the taste that it asserts emphatically demonstrates that it can excel in this. Dioscorides too wrote that arisaron had considerable bitterness and so, rubbed on, reduced corroding sores and that a salve, very efficacious against ulcers, was made from it. He also says that its root, applied to the private parts of any animal, damages them. Pliny too has written that arisaron heals running sores, burns, and fistulas. He also says that mixed in an ointment, it curres running sores.”

For a great description of Fuchs’ book and work, take a jump to the Glasgow University Library write up of Leonard Fuchs

1526: The Grete Herball: a tendril of ancient herbal traditions reaching into 16th century England.

A Paper-Bound Time Machine.

Published initially in 1526 by Peter Treveris, the Grete Herball is a translation of a much earlier French herbal; Livre des Simple Medicines, which was already over one hundred years old when Peter Treveris translated it into English.

The French herbal was itself a translation of an even earlier work from the 12th century; Circa Instans, a work from the Salerno tradition combining Western (i.e. Greek)-based herbal lore with incoming Arabic herbal knowledge.

Circa Instans was written by an Italian medical practitioner, Matthaeus Platearius and is itself based largely upon a work called De Gradibus Simplicium. This work was written by a Tunisian doctor known as Constantine the African.

Based in the medical hotbed of Salerno in Italy, Constantine was a medical professor who translated many works of Arabic origin into Latin, which had a huge influence on subsequent medical practice and literature. Constantine’s De Gradibus Simplicium is an example of this, being itself a translation of a 10th century Arabic work, de Gradibus by a Tunisia-based Muslim physician known as Ibn Al Jazzar. This in turn, contained much herbal lore originally found in Dioscorides’ work.

Despite its date then, this is effectively a pre-medieval herbal brought back to life hundreds of years after its original time. It gives us a great insight into the language of Middle English botany in all its diasporic freedom.

Its description of Arum is in wonderfully archaic English.

‘It is called De Iaro. Cucko’we Pyntell, Arus. Calfs foot. It is hot and dry in the degree. It is also named aron. Some call it priestes hode. For it hath as it were a cape and a tug in it lyke a serpentyne of dragos, but serpentyne is longer. It groweth in moyst places and dry on hyis, under hedges and may be gathered in winter and somer.

‘It hath greate vertue in the leaves, but moe in its rote, but yet it hath more vertu in the knottes that be about the rote. It is gathered and clouden in middes and dyed.’

Arums Medical Uses.

The medical uses for Arum in the Grete Herball mostly mirror earlier works such as those of Dioscorides, but two are worth repeating.

For emozroydes [haemorrhoids]:

‘For emozrodes or pyles all evil of the fundiment, seeth this herbe and bathe y Paciet in the same to y navel, Dr bynde the herbes hote in a clothe and let him sit thereon.’

To bring on the menses:

‘To cause menstrues to flewe out the iuyce of this herbe into the conduyte with an instrument yzo pze for it oz medle it with the medecine called benet and than bled, oz with cotton wette therein and to minisstered.’

The First Illustrated Plant Guide in England (but not very good),

The Grete Herbal was also the first illustrated book on plants to be printed in England and contained 477 woodcuts. Unfortunately, this wasn’t as useful as it might sound. 70 of these were not actually of plants at all. Those that were, were often very poor copies of illustrations found in the earlier French, German and other early herbals and manuscripts on which this book was based. There are numerous discrepancies, some of which are pointed out by the printer, while elsewhere, the same illustration is used to identify a number of different species (albeit similar looking ones such as rice and wheat, though here is exactly where one would want accurate drawings). Useful illustrations are found for clover, rose, strawberry and water lilly. Just those ones for which pictures are probably not really needed.

The Same Book, evolving into a Different Book.

This stream of ideas found in this book, with its curious mixture of botany, myths, fables and factual herbal instruction, flows as a direct lineage from Dioscorides himself, meandering through the Arabic herbal traditions, whirlpooling back to Europe and finally disappearing in the Medieval period before resurfacing in the modern ages of the Elizabethan era.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

1525: The most pirated book of the 16th Century (and no, it’s not the bible).

Book pirating really began in earnest in the 1400’s, once the invention of the printing press made the tedium of hand copying manuscripts unnecessary. What a great boon to unscrupulous book publishers that was.

In every field of literature the relative ease of printing meant that existing manuscripts along with bright-new works could suddenly be mass produced, expanding the accessibility to knowledge to more and more people. The new masters of the art: the printmakers, were quick to realise its potential.

The First Printed Herbals.

The first herbals produced with this new technology were often simply printed reproductions of works which had already been in existence in manuscript form for hundreds of years. They are known collectively as the ‘Incunabula Herbals’, incunabula meaning ‘wrapped in swaddling clothes’, and so rather lovingly referring to works produced in the first 50 years of the printing press: the newborn books.The sudden ability to reproduce these ancient manuscripts, effectively en masse, was to turn the status quo of the previous two thousand years on its head. For the first time people were able to produce a copy of say, Dioscorides’ great work, effectively on demand, in as many copies as desired, in relatively no time at all (compared with how long it would take a scribe to copy out the entire manuscript afresh) and without having to pay a scribe for his time either. It must have seemed incredible, dangerous and exciting all at once. These were heady times for the printers and they lost no time in letting it go to their heads.

New writers were also quick to get in on the act, though all was not rosy for such early authors. Just as early manuscripts were copied by hand from manuscript to manuscript, the printing press only amplified this time-honoured means of reproduction. Within months of a popular work being printed, copies were produced by other print houses and they seldom gave any credit for their original sources. Many writers and publishers would produce so-called ‘new’ works which were predominantly reworkings of existing publications or even just translations of works in other languages, producing a rolling tumbleweed of copying, mis-translations, half-truths, garbled medicinal information and, with few exceptions, illustrations of a steadily deteriorating quality. Plagiarism was the name of the day and the copying of others’ work clearly has a very long precedent indeed.

Bankes’ Herbal, the first herbal to be printed in England.

One particularly unfortunate victim of this was the Richard Bankes, author of his very popular and high-quality eponymous herbal published in London in 1525. Seemingly an original work – or at least based on an otherwise medieval source manuscript – it ends with the words ‘Imprynted by me Rycharde Banckes, dwellynge in London, a lytel fro ye Stockes in ye Pultry’. It was the first herbal published in England and contained useful botanical information on the plants and their medicinal properties and often gave a greater amount of factual information than many other existing and more famous herbals. It also must rank as one of the most pirated books of the 16th century.Over the next 25 years an impressive number of different editions of Richard Bankes’ work were produced. Unfortunately not one of them was by Richard Bankes. These copies were issued by other print houses and, to disguise their provenance, they were given different titles and ascribed to different authors. Sometimes they even claimed to be works by classical writers from Ancient Greece or the personal practice notes of eminent doctors. Once inside the covers however, they were simply copies of poor old Richard Bankes’ herbal.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

(above image: Lviv book market. The statue is of Ivan Fedorov; the bringer of printing technology to Lviv.)

1500s: The Elizabethan Ruff, Manicured Beards and Arum Starch #2

Part 2: Starching Your Beard, Slovenly Solicitors and the Elizabethan Mr Angry.

Beard Starching.

Beard starching. Never done it? The Elizabeth era was the prime time for men to display their creativity in beard shaping, a somewhat neglected manicure amongst the gentlemen of today. A man wishing to sculpt his beard into a suitably fashionable and attractive shape had to take into account a number of considerations. Firstly there were the Elizabethan class dictates, so that where he lived and what profession he held played an important role in how his beard might be manipulated. Such important social signals were not to be overlooked. That decided, he was then free to enter the constantly changing fashion race of sculpting his beard into different angles, shapes, cuts, coils and contortions.

‘having starched their beards most curiously...’

To ensure such facial architecture would remain in place, men would stiffen their beards with starch. Now, there is a persistent rumour that it was specifically Arum starch that was used for this. The source of this is usually Cecil Prime, who refers to a preface by Thomas Nashe in Robert Greene’s Menaphon of 1589. The actual sentence is this:

‘Sufficeth them to bodge up a blank verse with ifs and ands, and otherwhile, for recreation after their candle-stuff, having starched their beards most curiously, to make a peripatetical path into the inner parts of the City, and spend two or three hours in turning over French dowdy, where they attract more infection in one minute than they can do eloquence all days of their life by conversing with any authors of like argument’.

A life of reckless debauchery

Robert Green was, along with Marlowe, one of the most established playwrights and dramatist of the time, and was known for writing very popular love tales (the Elizabethan equivalent of Mills and Boon romance) and for living a life of reckless debauchery and continual criticism of others around him – so much so that even he confessed that he was ‘unable to keep a friend’. There was a notable contrast between his life and the dreamy, happy romantic world of his writings, but he was acknowledged as a genuinely talented writer and his works were undeniably popular. Menaphon in particular was the most accomplished of his ‘romance’ novels.

Thomas Nashe, on the other hand, was relatively unknown at the time but was part of a contemporary circle of London-based writers known as the University Wits (a group of which both Greene and Marlowe were members). A Cambridge graduate, he has been described as a ‘journalist born out of time ... with a brilliant and picturesque style’. He wrote with a fierce satire of the figures and society around him. His preface to Greene’s Menaphon gave him his big break and he used it to put down Greene’s critics and ridicule other writers of the contemporary scene. In the quotation above, he is actually referring to lawyers who leave the legal profession to become writers, saying that they will kill even the best writing stone dead. He then goes on to say how they starch their beards before heading into town to sleep with prostitutes and return with venereal diseases. This gives a good idea of Nash’s style, both in his writing and his approach to life. Some have said that this was a coded reference to the young Shakespeare (particularly as Greene himself had given Shakespeare a hard time on occasion). However, we know little of Shakespeare’s early life and there is no evidence of him having worked as a lawyer previous to his life as a playwright.

Despite the wealth of information about and by Nashe, he does not explicitly state anywhere that it was specifically Arum that was used as a beard stiffener. We can only assume that it was, given its popularity and penetration into the lives of Elizabethans at that time and their fascination with exploring the limits of its stiffening properties.

As an aside, such was the zeitgeist of Arum’s starch-stiffening fame that at one time, according to Boyce, a relative of Arum (alpinium) was used in Scandinavia specifically to stiffen clerical collars. As a result, he says, it can often still be found growing around old church sites.

The Elizabethan 'Mr Angry'.

We have already read (in the last post) that objections were raised about the use of Arum starch in ruffs because of its affect on the laundry maids' hands. Some took a dislike to ruffs themselves because they believed that such items were the direct work of the devil. A now infamous pamphlet was distributed at the time by a puritan Christian called Philip Stubbes. It makes for amusing reading; he was the original ‘Mr Angry’ of every local newspaper letters page. In his pamphlet he gives his views on everything that annoys him, with ruffs singled out for special treatment. ‘The devil, in the fullness of his malice invested these ruffes’ he said, before going on the describe this new-fangled substance they call starch (another invention of the devil): ‘The one anchor piller wherby his kingdome of great ruffes is underpropped, is a certaine kinde of liquide matter which they call Starch, wherin the devill hath willed them to wash and dive his ruffes wel, which when they be dry, wil then stand stiffe and inflexible about their necks’. That was just the preamble. Ruffs (amongst many other things) really did get Mr Stubbes worked up into quite a stiff lather: ‘Ruffs that go flip-flap in the wind, and lie on men’s shoulders like the dish-clout of a slut’. And so it went on.

Oh Arum – in trouble again. The devil’s plant, indeed. Philip Stubbes need not have worried. By the end of the Elizabethan era and the new reign of James I, the use of Arum – along with the giant ruffs it had once supported – shrunk and diminished into the realms of history. Laundry maids across the country sighed with relief and Arum was largely forgotten.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

Above photograph by Fergus Drennan. More of his Arum food photographs can be seen in the book and his work with wild foods can be viewed at fergustheforager.co.uk

1500s: The Elizabethan Ruff, Manicured Beards and Arum Starch #1

Part 1: How Arum made 5ft wide Elizabethan Ruffs possible.

image: wikimedia.org http://bit.ly/196qHVa

The Elizabethan era was to fashion what the Precambrian era was to evolution: a time when a whole variety of strange forms came into being, had their fun and then promptly died out, leaving only those more practical designs to pass on down the ages. Ruffs are the trilobites of fashion: in their day widespread and successful, today well known and generally much loved by current generations. They are the ‘type fashion’ of the era and, like trilobites, completely extinct.

The ruff evolved from the ruffle. The word and the garment, hand in hand defining the fashion of an era. Ruffles appeared early in the 13th century, as simple strips of crimped trimming added to sheets as a decoration. Fittingly, the word originates from the Germanic ruffelen, meaning ‘crumpled’. By the 15th century, ruffles were used around the neckline of items of clothing such as chemises, those smock-like precursors to modern-day shirts originally worn by women. They served the distinctly practical purpose of saving a wearer’s ‘shirt’ or top clothing from becoming soiled around the neckline (think how modern shirt collars suffer). Being detachable items they could be washed separately, thus avoiding the need to launder a whole smock or shirt. Very sensible, those Tudors.

With the quickening of the Elizabethan era, ruffles left their utilitarian roots behind them. Hearing the call of destiny, they became ever more ornate and distinctly non-utilitarian items of fashion and status. Bedecked with jewels and arranged into tiers, ruffs (as they were now called), sported varied shapes, numerous styles and a range of colours, all peculiar to the wearer’s class and gender. Such were the dictates of Elizabethan society on class and clothing that the yellows, reds and purples favoured by the upper classes is said to have given rise over time to the ‘Lords and Ladies’ name for Arum.

The most extreme ruffs grew to become over a foot (25 cm) wide: supported by internal frames to bear their weight. Such constructions could often comprise over 15 feet (5 m) of cloth. Cecil Prime describes how bearers of such ruffs could hardly walk or bend whilst wearing them. At one point it was clearly felt to be getting out of hand and Queen Elizabeth banned such extra-wide ruffs. All jolly good fun no doubt, but such experiments in fashion were made possible only by a single discovery – Arum starch.

We do not know how or when, but at some point it was realised that Arum was not only a source of starch but that it produced such a very fine-grained and white starch that it was on a par with that derived from rice and wheat and, indeed, from arrowroot itself. Arum quickly became prized for its suitability for laundry starching, giving a strong and stiff structure to the cloth. So pronounced were its stiffening qualities that, combined with the newly imported Dutch starching techniques, anything seemed possible. People began experimenting. Ruffles seemed a good place to start: thus was born the ruff. The fashion designers of Elizabethan times embraced Arum wholeheartedly and it is no exaggeration to say that it is Arum that made the whole wonderfully outlandish extravagance of Elizabethan ruffs possible.

Demand for Arum was considerable for a time, but its super-starch strength came with a significant cost due to its effect on people’s skin – not the skin of the lords and ladies, but the skin of their washerwomen. Unlike rice or wheat, Arum contains the incessantly irritant calcium oxalate crystals. These needle-shaped crystals are of such tiny size that they penetrate into the very pores of the skin whereupon they cause intense itching, chapping and blistering. They are equally damaging whether one is handling the leaves or the roots, and Arum starch soon became renowned for causing severe and painful blistering to the hands of the laundry maids who made it. Gerard stated, ‘It choppeth, blistereth and maketh the hands (of the poor launderesses), rough and rugged and withall smarting’.

In part 2: Starching Your Beard, Slovenly Solicitors and the original Elizabethan Mr Angry.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

c.1500: Arum maculatum given its first official name of Arum officinarum by Matthaeus Lobelius.

The botanical name Arum maculatum first appears as far back as 1588, when Tabernaemontanus used it in his great herbal: the Neuwe Kreuterbuch, the illustrations of which went on to be used in Gerard’s herbal of 1597. At that time, the name was used in a fairly loose fashion and didn’t necessarily refer specifically to our modern Arum maculatum.

The plant was more commonly known, when it was specifically named at all, as Arum officinarum – or at least it was so called by Matthaeus Lobelius, the French botanist who began the first concerted attempt at botanical classification during the 1500s. In reality, the name didn’t stick, but it does tell us that it was already the ‘type plant’ for the arum genera: the reference or starting point to which all other varieties were compared. The name and the plant as we know them did not come together until 1753, when Linnaeus formally named the plant as such in his famous Species Plantarum, which defined the format for scientific classification that is still used today.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

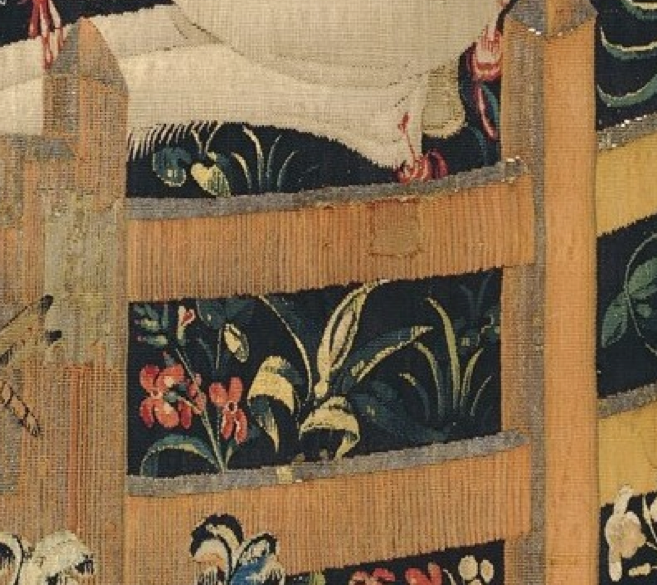

1495–1505: The Unicorn Tapestries produced. Arum depicted in the sixth tapestry.

Quite possibly the most beautiful example of Arum appearing in art and one where Arum is depicted accurately as well as artistically, is in the last of the so-called ‘Unicorn Tapestries’. This series of seven tapestries represents one of the pinnacles of medieval art, each hanging measuring just under 4 x 3 metres, woven in wool and silk with silver and gold threads. Created between 1495 and 1505 in Brussels or the Netherlands, it is still a mystery why and for whom they were made or even whether they were originally intended to be hung together at all. It is known that for centuries they were in the possession of a French family by the name of La Rochefoucauld, who hung them in their family home in Bordeaux. In 1789, amidst the chaos of the French Revolution their chateau was ransacked and the tapestries stolen.

The family returned to their chateau in 1855 and made it known around the locality that they wanted the tapestries back and would pay for their return. No questions asked, presumably. Astonishingly, all of the tapestries were still in the hands of families of local farmers and the Rochefoucaulds regained possession of their wonderful hangings. Even more remarkably, it turned out that these incredible tapestries, at this point some 350 years old, had been used by the local farmers like old rags; for protecting piles of potatoes in barns and wrapping around fruit trees in spring to protect them from frost. For 65 years. Despite such unintended and seemingly abusive activities, the tapestries were still in good condition and generally had not suffered undue harm. The family hung them in their home once more until 1922, when they sold them to John Rockefeller for $1 million. After enjoying them in private for 15 years, he donated the tapestries to their current home.

The tapestries are today displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (in New York) and depict the hunting and killing of a unicorn by a group of noblemen. The sixth tapestry shows the unicorn as dead; killed by the noblemen and brought back to the castle for the lord and lady. In keeping with Arum’s symbolic powers, however, the seventh and final tapestry depicts the unicorn as alive and well, seemingly resurrected but now contained by a fence and chained. It is, however, a very low fence and the chain is very loose; the implication being that if it wished to escape, it could do so. Many plants are depicted within the fence with the unicorn and Arum is one of these, very visible, in full fertile glory, beside the resting unicorn.

This particular tapestry (and Arum) also makes an appearance in the film Harry Potter and the Half-blood Prince, where it is seen covering the wall outside the ‘Room of Requirement’ with the character Malthoy standing before it. It is also glimpsed against the walls in various Harry Potter ‘house’ common rooms. A high-resolution image of the seventh tapestry depicting Arum can be seen on the Metropolitan Museum’s website at http://bit.ly/17ts7tu. The image above is a screen shot of a zoomed in portion, showing the Arum within the fence.

The main page for the museum’s section on the tapestry is here: http://bit.ly/OYQh6b

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

First Herbal with Original Pictures for 1000 Years.

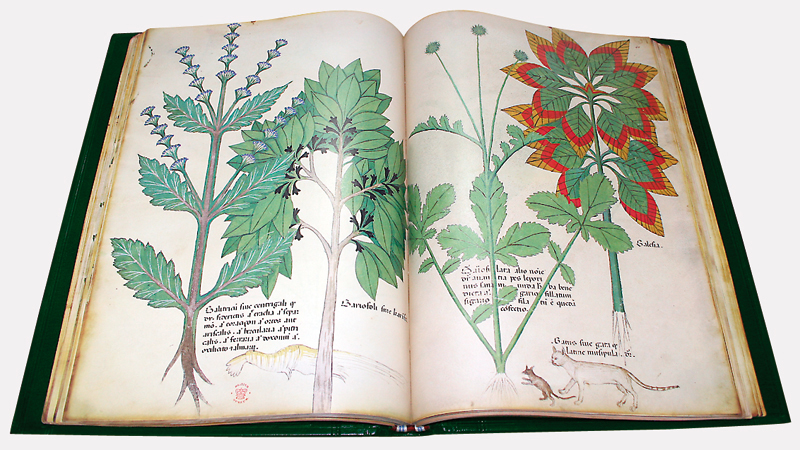

1440: The Tractatus de Herbis is published.

Until the 15th C , with its invention of the printing press and the subsequent explosion of Elizabethan era herbals, there were basically two main herbals (at least, illustrated ones) doing the rounds in the ancient world: Dioscorides’ Materia Medica, which was the main body of work in both the Greek and Arabic traditions and, in the West at least, the Herbarius of Apuleius Platonicus, which was produced somewhere around the 3rd - 4th C. These were the ‘big guns’ on any respectable herbalist’s bookshelf even though one was essentially a copy of the other, along with pretty much every other herbal available. Then along came the Tractatus de Herbis.

There is a single significant reason why this manuscript is considered to be such a remarkable herbal: its illustrations. To understand why, let's backtrack a little. Back to ancient Greece, back to before even the great Dioscorides produced his magnificent work. Back to around 350 BCE. The time of Aristotle, Plato and Theophrastus.

This was the time when the very earliest herbals that we know about were produced. None of them have survived and today we know about them only through references in later works. They are thus evocatively known as 'ghost works'. One thing that we do know is that they were illustrated and their illustrations were incorporated (i.e. copied), into the great herbals that do survive; Dioscorides’ work being the main example. What was remarkable about them is that these illustrations were based on observations of the actual plants themselves. Amazing eh?

The bizarre thing is that once these pictures had been produced, common consensus seemed to be that that was that; job done. The same illustrations were then just copied from manuscript to manuscript down the ages - for almost a thousand years. Not surprisingly, many became so derivative that the plants they were supposed to be illustrating were completely unrecognisable. That nobody really minded this is evidenced by the fact that every now and again, someone thought that the, by now highly abstract and botanically useless, pictures were so beautiful they would make a nice book just on their own without all of that distracting writing and herbal lore.

It was not until the 14thC (a thousand years after the original illustrations), that someone thought that perhaps it might be a good idea when writing a herbal to put in illustrations which were not 1000 year old copies of copies of copies but instead were pictures of the actual plants, so that a person might be able to use the pictures to identify the plants. Thus was born the ‘Tractatus de Herbis’.

It is a beautifully illustrated book specifically designed to show the different plants used in medicine as accurately as possible so that practitioners of different nationalities, languages and reading skills could properly identify the right plant.

This was clearly a far too new-fangled idea because it did not really catch on for another two hundred years, when the production of modern herbals and the development of a more ‘modern’ botanical-medical attitude was in full swing. The pictures from this herbal did however get copied themselves and made into yet another picture book; without any of text to get in the way.

It now resides in the British Library.

A number of images can be seen here

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

1256: Albertus Magnus writes De Vegetabilis

Less a herbal than an original work of early botanical science. He does mention Arum in his manuscript, stating that it gives protection against all kinds of serpents. “Arum maculatum basilicas 'is a plant, which dracontea' or serpentaria said, having Ionga leaves, and in the midst of a broad, but fastened to the utraraque extreraitatem. But it is in the flower of the saffron, and he does many things in the seed grains, as a cluster, and they are its first green, red, and afterwards, when they are ripe. Now the first in the pods, it bringeth forth, which is like the latter part of the serpent, as at the end of the tail of the serpent, and has a variety of his own in a tree trunk of the serpent. And the serpent 's bite has power against the juice thereof, and also it is said that they must be carried safe from all the serpents.”

The site ‘famous-mathematicians.com’ describes him thus: “He wrote more than seventy books and papers and if combined his written work add up to twenty two thousand five hundred pages...He not only taught theology but also lectured on mathematics, logic, economics, rhetoric, ethics, zoology, chemistry, mineralogy, phrenology, politics, metaphysics and many other divisions of science. He also did some work in astronomy, realising that the Milky Way consisted of stars. He also worked in the fields of geology and botany doing a substantial amount of work in both. His written works includes ‘Physica’, ‘Summa theologiae’ and ‘De Natura Locorum’

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

1250. How a family in Wales were taught healing by a fairy woman and passed their skills on for 400 years. The Physicians of Myddfai.

As well as the Leechbook, the other healing tradition of which we have written record is that of a magical healing family from Wales. The Physicians of Myddfai were a family of healers and physicians from the parish of Myddfai in Carmarthenshire in Wales. They were said to have descended from three sons whose mother was one of the fairy folk to whom their father was married until she returned to her lake.

In 1897, a John Pugh published a translation of a transcript of an interview which took place in 1743 with a John Jones; the last surviving member of this family line. The resulting translation was called The Physicians of Myddvai.

The Fairy Wife.

The beginning of the family's story, in brief, has its origins with the sole son of a poor widow, who meets a fairy woman coming out of a lake in the mountains, where he is tending his cattle. With his mother's help, he wins her hand in marriage and they have three sons. The marriage is destined to last only until he has 'struck her three times'. After the third strike, she leaves him and returns to the lake. However, she does come back on occasion to visit her children. Upon the eldest, she bestows her healing skills and knowledge.Royal Approval.

The eldest Son was called Rhiwallon and his sons became Physicians to Rhys Gryg, Lord of Llandovery and Dynevor Castles, who gave them rank, lands, and privileges at Myddvai for their maintenance in the practice of their art and science, and the healing and benefit of those who should seek their help, thus affording to those who could not afford to pay, the best medical advice and treatment, gratuitously. Such a truly Royal Foundation could not fail to produce corresponding effects. So the fame of the Physicians of Myddvai was soon established over the whole country, and continued for centuries among their descendants.The Welsh Healers.

The family practised their fairy-derived healing skills from at least the 13th century until the mid 1700's. The last practising descendent was John Jones, a respected surgeon, who died aged only 44 in 1789. He and his family's gravestones can still be seen in the parish churchyard today. This line of healers represents a distinct and separate and equally ancient healing tradition of these lands. It contains, like the Leechbook, a mixture of herbal cures and deep superstitions as well as strange rituals of cure.Arum.

Arum is mentioned in the recipes of The Physicians of Myddfai. As in the Leechbook it records its use for dissolving growths and blockages in the body by boiling the root in wine and drinking the decoction over three days."Take the root of the dragons, cut them small, dry and make into a powder, take nine pennyweights of this powder, boil in wine well and give it to the patient to drink, warm, for three days fasting, and it will cure him; and I warrant him he will never have it again."

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

Arum, Fairy Lamps and the ever-lasting spring: the legend of the Anglo Saxon St Withburga.

One of the more religious mentions of Arum is the plant’s association with St Withburga. Withburga was the youngest of four daughters of the Anglo-Saxon king Anna. When he died in 654, his eldest daughter Ethelreda inherited the Isle of Ely and founded the monastery and abbey there. Withburga meanwhile founded a nunnery and church at Dereham in Norfolk. Typically (for a fairy-tale type of legend) she was the poorest of the four sisters and during the building of her nunnery she did not have enough money to buy food for the workmen. After praying for divine intervention, two young does appeared from the surrounding woodland and allowed her maids to milk them. This sustained the workmen in their labours until a jealous local landowner chased the does away with his hunting dogs.

Tradition does not say whether this was after the church was completed or before and if before, we know not how the poor workmen continue to be fed. Tradition does record though that the landowner’s experience of divine retribution was swift, for shortly afterwards he was thrown from his horse and broke his neck.

No further miracles are recorded until long after Withburga died and had been buried in her church. Fifty years passed without event, until her body was discovered to be as fresh as when it was first interred. She is even reported to have blushed when a workman caressed her face with his finger. At this point, events take a dramatic turn.

News of the saint’s undecaying body spread quickly and the little church surrounding her fresh remains became a popular destination for the pious. This didn’t go down terribly well with the increasingly powerful Bishop of Ely and in 974 he ordered that Withburga’s body be forcibly removed and brought to Ely, ostensibly so that she could rest alongside her sisters who were all buried there. Another reason is thought to be so that the Bishop could enjoy the prestige and profit to be made from the increasing numbers of pilgrims journeying to visit St Withburga’s miraculously undecaying body. The Bishop of Ely’s monks arrived at the church with a cover story of wanting to celebrate St Withburga’s presence and miraculous preservation. They plied the locals with food and drink. And more drink. And more still. When everyone had fallen into a drunken stupor (but having somehow kept themselves sober), they stole the body of St Withburga and proceeded to take her back to Ely. Part of the journey was along the river Little Ouse. Richard Mabey, in his book Flora Britannica, includes a tale from E.M. Porter’s Cambridgeshire Customs and Folklore (1969) that describes the part played by Arum in this drama. The monks from Ely rested at Brandon, whereupon nuns from the nearby convent at Thetford arrived and covered the body of the saint in Arum ‘flowers’ (possibly due to an at the time recognised symbolism with death?). As the boat moved on, these fell from the body and took root in the river banks. Eventually the banks were covered in Arum blossoms that glowed with a pale, white light along the entire length of the river from Thetford to Ely. Meanwhile, back at Dereham, a spring had appeared where Withburga’s body had lain. This flows still to this day and has never run dry.

From this legend come the Cambridgeshire names for Arum of Fairy Lamps and Shiners, from how the flowers glow at night. Another name is River Fairy Lamps, said to come from Irish workmen in the 19th century who were brought to the area to drain the fens and discovered along the trail of St Withburga the Arum ‘flowers’ glowing still, as perhaps they still do to this very day ...

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

400 CE. The Anonymous Herbal Written by a Roman African and Copied by Hand for Over 1000 years.

The Singularity of the Printing Press.

Prior to the invention of the printing press, herbal manuscripts were reproduced by being copied, written, drawn and bound by an individual's hand. There were rare, expensive and valuable items; each one at least a little bit, unique.

The printing press changed all of this. It was a new industry, creating a new world and ushering in new possibilities. In every field of endeavour the relative ease of printing meant that existing manuscripts along with bright-new works could suddenly be mass produced, expanding the accessibility to knowledge to more and more people. The new masters of the art: the printmakers, were quick to realise its potential.

The Incunabula Books.

The first herbals produced with this new technology were often simply printed reproductions of works which had already been in existence in manuscript form for hundreds of years. They are known collectively as the ‘Incunabula Herbals’, incunabula meaning ‘wrapped in swaddling clothes’, and so rather lovingly referring to works produced in the first 50 years of the printing press: the newborn books.

The Herbarium of Apuleius Platonicus.

One of the first herbals of these 'new born' books to be given the 'mass-production' treatment was a small volume known as the Herbarium of Apuleius Platonicus.

This was effectively a popular 'everyman's' version of Dioscorides' master tome. The original author is unknown, the name 'Apuleius Platonicus' being only a pseudonym, though some evidence points to the author being a writer from (what is now) Algeria, in Roman Africa called Lucius Apuleius. The herbal does also contain a number of herbs found in Northern Africa, but no one really knows for sure.

Copied by Hand for over 1000 years.

The content of the early hand written manuscript was drawn (ie copied) primarily from Dioscorides and Pliny and so popular was this herbal that, if it did indeed first appear in the 5th century, and was first printed in the 15th century, then it would have been in continual production, through being copied by hand, for over 1000 years by the time it was first printed.

It was one of the first, if not the first, translations of the Mediterranean herbal tradition into English and was around at the time of the Leechbook we have already looked at. When printed in the 15th century, it also became one of the first illustrated printed herbals, though the illustrations, being copies of copies of copies, were more 'artistic' than 'botanical'.

A copy of an English translation exists today in the British Library. It of course mentions Arum, as Dracunculus, giving much the same information as Dioscorides.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

Faery Lore, Elf Shot and Arum

9 CE: Bald’s Anglo Saxon Leechbook

Of our Anglo-Saxon herbal knowledge and practices, only a fraction has survived to this day. Most of what was known was never written down and much of what was is long destroyed, either deliberately by the early Normans or by the simple passage of time. What remains gives us a teasingly small glimpse into the world of our Anglo Saxon ancestors. Into a world of great herbal knowledge intimately intertwined with ancient rituals, deep superstitions and a firm belief in the elven folk.The Anglo-Saxon Leechbook of Bald is a manual of medical practices from the time of Alfred the Great. It exists only as a single manuscript, now housed in the British Museum and is the earliest known written medical lore from England. It is called ‘Bald’s’ leechbook because Bald was the person who ordered it to be compiled, by a scribe named ‘Cild’.

It may well be that it was created as part of King Alfred’s drive to create a more educated and equal society in his Kingdom. It is the oldest medical text known from the British Isles.

Leeches and Medical Bills.

Contrary to today’s usage, the word ‘leech’ in the title does not refer to the bloodsucking variety, but is the modern rendition of the Old English word 'laece', the word for a healer. This in turn is derived from the root word 'laekjaz', meaning enchanter or ‘one who speaks magic words’ (Polington 2000). 'Laece' is also related to another Old English word, 'lac', which relates to the practice of sacrifice and the offering of a gift or wealth.Here we come upon a very ancient association between magic, healing and the making of sacrifices, either to the Gods or to the ‘leechmen’ in return for health. With the Old English word 'laece-feoh', or ‘leech fee’, it illustrates the long-standing power of healers and doctors to extract wealth from patients – an ability retained to this day.

Inside and Outside Diseases and the Pagan Charms to Cure Them.

The manuscript itself is split into three different books; the first two cover the treatment of external and internal problems, respectively, with both books arranging the remedies in a head-to-foot fashion. The third book is a collection of magical charms, rituals and folklore as medical remedies. These are a fascinating collection of our ancestor’s beliefs which stem from a north european bedrock and show little of the Mediterranean influence so prevalent in other herbals. The herbal charms, superstitions and rituals recorded do not date from the 9th century but instead are an echo of a much older, pre-Christian time, dating back to the days of Beowulf. They form a curious mixture of Christian beliefs and pagan practices which were both swirling around together in these tumultuous times.Many illnesses were held to be the result of elf-shot, so much so that the longest chapter in the third book is entirely devoted to such elf-caused maladies. These were not the tiny gossamer fairies of Victorian times, but dark and powerful beings of nature who, more often than not, were unfriendly towards mankind. It was a ‘time when grown men believed in elves and goblins as naturally as they believed in trees’. (Rhode 1922)

The Knowledge of Herbs.

One of the notable features of the book is that it makes references to earlier ‘leechmen’, naming some of them and the remedies which they taught. Such references indicate that the records we have in Bald’s Leechbook are based on an even older tradition of healing which seemed to have already organised itself into a kind of professional body with its own ‘authorities’: an insight into Anglo-Saxon society for which we have no other evidence. Even more remarkable is that the Leechbook is written in vernacular Anglo-Saxon, not Latin, demonstrating that there was already a section of society that was literate yet separate from the Roman–Latin tradition of mainland Europe. That their knowledge was extensive is evidenced by the fact that even the very limited Anglo-Saxon literature which has survived mentions around 500 different plants, a number exceeded only by Dioscorides. Even famous European herbals such as the Herbarium of Apuleius described only 185 different plants and this was one of the most popular herbals in Europe.Arum in the Leechbook.

The Leechbook is, amongst many other things, a rare example of a tradition of healing and herbal knowledge in Europe not derived from Greek/Arabic sources. The Regarding Arum, it says:‘If a strong potion lodge in a man, and will not come away, take the netlierward part of celandine, and leaves of libcorn or arod, boil in ale, add butter and salt, give to drink a cup full of it warm.’

Further Reading for Bald's Leechbook and Anglo Saxon herbal practices.

The Old English Charms and King Alfred's Court.

http://hompi.sogang.ac.kr/anthony/mesak/mes101/Nokes.htm

Stephen Pollington’s book; Leechcraft, Early English Charms, Plantlore and Healing. Published in 2000 by Ango-Saxon Books.

Cockayne’s Anglo-Saxon leechdoms, wort cunning and starcraft of early England, from 1864. Available at: http://archive.org/details/leechdomswortcun02cock

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

Medieval File Sharing. How a single manuscript became the most copied herbal in history.

“Dioscorides Recommends the juice of the seeds for earache and for adding to a drink to aid abortion, the root for coughs and the leaves to eat and for wrapping cheese to preserve it. He also states that Arum is an aphrodisiac and will excite a vehement desire when drunk with wine. Dioscorides also states that rubbing the root, specifically, on one’s hands, will protect one from being bitten by snakes. He describes it as being suitable as a vegetable, with the leaves either being preserved in salt or boiled. The root was also edible, particularly when roasted with honey. Dioscorides also says that the leaves are good to eat and will preserve cheese if it is wrapped up in the leaves.”

Around the same time that Pliny produced the first volume of his great encyclopaedia, there occurred the third and probably most significant publication of this period. This was the creation of a herbal called De Materia Medica, written by a Greek soldier and army doctor known as Pedanios Dioscorides of Anazarba. This single work was to have more influence on herbal literature than any other for the next two thousand years.

It was in Dioscorides’ great manuscript that the medical herbal found its foundation. Dioscorides had travelled and practised widely for many years in his career as a physician and soldier before setting down his experiences on parchment around 65 CE. Dioscorides incorporated material from a number of earlier authors such as Theophrastus, Crateus, Diocles and the Herbal of Sextus Niger. That said, this was not just a compendium of earlier herbals. Dioscorides’ five-volume work included the results of his own investigations, experience and observations and contains details of around 600 different plants, which is around 100 more than anyone else had previously described. He also presented a system of botanical classification which was essentially pharmacological, grouping the plants together according to their medical properties. This was so far ahead of its time that, in subsequent copies, scribes ignored Dioscorides’ ideas and reverted the manuscript to the traditional alphabetical order of listing the plants. So much for innovation.

The original manuscript of Dioscorides has long since disappeared. The earliest complete version to have survived is a manuscript from 512 CE known as the Juliana Codex or the Codex Vindobonensis. Few other books have such an illustrious history. It was produced as a gift by the local townspeople of Constantinople for Juliana Anicius in response to her construction of a local church. Juliana was the daughter of Flavius Anicius Olybrius, who was briefly the Roman Emperor of the Western Empire in 472 CE.

The manuscript is around a thousand pages in length and magnificently illustrated, with almost 400 full-page colour paintings opposite the plant descriptions. Already, the plants have been arranged alphabetically, ignoring Dioscorides’ original classification system. Extra material from other ancient authors has also been added, including a guide to over 40 Mediterranean birds - not what one would expect to find in a herbal and definitely not part of Dioscorides’ original text. Many of the illustrations though are thought to be copies of those found in the now extinct Rhizotomicon of Crateus.

Following its creation and presentation to Juliana Anicius, the manuscript then disappears from history. We don’t know who owned it or to what countries it travelled, yet a measure of how useful and valuable it was considered is that by the time it resurfaces, over a thousand years later in 1652, its parchment pages are teeming with handwritten notes and amendments in over 20 different languages including Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew and French. It had clearly passed through a wide variety of privileged hands. Remarkably, rather than sitting forgotten on the dusty shelves of a library, this single individual book had been in constant use for over a thousand years.

This use would seem to have taken its toll. At the time the book resurfaces into written history, it is the property of a physician in Constantinople who received it from his father; the personal physician of Süleyman the Magnificent (after the city came under Turkish rule in 1453). The manuscript was described as being in such a bad state that ‘no one, if they saw it lying in the road, would even bother to pick it up’. These were the words of an ambassador of the Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, who wished to buy the manuscript but could not afford the 100 ducats being asked for it.

Such was the pull of this work though that by 1659, only 7 years later, the Emperor Maximilian II did buy it, to be held by the Austrian National Library in Vienna, where it has remained to this day. Though De Materia Medica was translated into a great many mainland European languages throughout the centuries, it was not until 1652-5 that a John Goodyear produced an English version, writing below the original Greek with a line-by-line English translation. The book took him 3 years to write and filled over 4000 pages, each one handwritten, yet strangely, it did not see the light of day until 1933, when it was finally published after being rediscovered in an Oxford library. Incredibly, this was the sole translation into English until a completely modern translation was published in 2000.

Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica was effectively the last word in herbal books for the next 15 centuries, dominating the contents of virtually all subsequent publications which mostly just copied directly from Dioscorides whilst adding some 'padding' of their own. It was the one source to which anyone aspiring to be, or working as, a herbalist would refer. In fact, despite that many of the medical recipes contained in it would not now be considered effective, it would be so slavishly copied, referenced and referred to that no real developments took place in the science of herbalism for the next 1500 years, because no one thought that anyone could do anything better. To question Dioscorides was unthinkable. To copy him, absolutely fine.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

A is for Arum in the first ever encyclopaedia.

Arum has its place in the first ever encyclopaedia. Known as the Naturalis Historia it was written by a Roman known as Pliny the Elder in around 77 CE. It is the only one of his works to have survived to the present day.

Pliny’s encyclopaedia spanned 40 volumes covering everything which was known about everything which was known. What makes Pliny the Elder such an amazing chap was that the entire work was written in the evenings when Pliny arrived home after his day job of administrating for the Roman Emperor. This must have involved longer hours and more stress than the average office management job does today, yet Pliny still found time and energy to spend his evenings writing and researching, creating volume after volume of his steadily growing magnus opus. What’s even more amazing is that he wrote the entire work by hand on parchment. Presumably by the light of just his oil lamps. I guess he did a bit more at the weekends but either way, his diligence is heroic and illustrates just how much more people achieved in the days before the Internet and TV.

Pliny’s encyclopaedia contained radical new concepts such as an index, it referenced its sources (a habit which was studiously ignored by most later herbals) and was written in a simple and accessible fashion to allow all to understand and benefit from its contents.

Arum has a number of entries in Pliny’s Naturalis Historia and he includes a large number of uses for the plant, drawn from a wide range of courses. The main section is in Book XXIV, Chapter 92, entitled The Aon: Thirteen Remedies. Pliny mentions here that Arum can be boiled in milk and used for cloudiness of the eyes, internal ulcerations and inflammation of the tonsils. It is recommended here for freckles, foreshadowing its use two thousand years later by the French as a skin cosmetic. Pliny quotes other sources as stating that Arum is good for difficulty in breathing and general conditions of the lungs and coughs, and restates its use as a facilitator of birth delivery for all animals. He also reaffirms the belief in Arum’s efficacy against serpents and snake bite.

Interestingly, he writes that already there is disagreement about whether Arum is one plant or many, on account of the different variations found around Europe, all quite similar but with noticeable differences. It is already known as ‘Aron’, ‘Dracunculus’ and ‘Dracontium’, and the Arum which Pliny mostly discusses is not the British Arum but the Egyptian Arum: a plant now known as Arum colocasia or Taro. This is a notable example of plant observation (along with that from Egypt) which was subsequently forgotten in the later herbals.

For more information, see the online version of Pliny’s works: http://bit.ly/Yh9Aud as well as the wiki page on his encyclopaedia at http://bit.ly/12nLyDL and a BBC podcast at http://bbc.in/dmyfUi

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

Arum's weird roots ; the deeper they go the thicker they get.

380–327 BCE Theophrastus, pupil of Aristotle (and both pupils of Plato), writes his Enquiry into Plants.

Arum first puts in an appearance in the early herbals and writings of Ancient Greece. It is from this time and culture that our knowledge of Arum’s herbal properties has its origins, firmly embedded within the roots of western culture. Three works by the founding figures of the great Mediterranean tradition of herbal medicine all mention Arum.

The first of these is by a student of Plato and Aristotle, named Theophrastus. Around 340 BCE he wrote his Enquiry into Plants, one of the earliest written attempts to codify the natural world and a precursor to modern botanical classification. It is also the earliest written reference we have to Arum. In his Enquiry into Plants, Theophrastus gives the first description of Arum being used as food and mentions a medicinal use: ‘The root of cuckoo-pint is also edible, and so are the leaves, if they are first boiled down in vinegar; they are sweet, and are good for fractures’.

Theophrastus was a philosophical botanist. In the style of his time, he debates whether Arum really has roots in the same way that other plants do because instead of tapering to a point, the way that ‘true roots do’, they instead get wider the deeper into the ground they go. Hence, they cannot really be ‘proper’ roots. An interesting point for discussion perhaps, but he didn’t really come up with any suggestions as to what else they might be, if not roots.

Theophrastus’ work was less a herbal as we might understand the term and more a very early work of botanical enquiry about the nature of plants. It was an attempt to understand, mostly from a philosophical viewpoint, how plants ‘worked’ and how they could be classified. Agnes Arber says in her book Herbals, ‘Aristolelian botany suffered from one serious handicap: an inadequate basis of actual fact’. She describes how Greek botany was created by philosophers who, being completely at home in the world of ideas, believed that any knowledge could be derived from thinking about ‘general principles of the world’ without any need for actual observation: ‘… it was left for workers in the apparently less promising field of medicine’ to do that. Ouch.

Perhaps there was some truth to that criticism but Theophrastus also embodied the spirit of intellectual investigation that the Greek's excelled in and in many ways set out the foundations of today's scientific worldview. He took issue with faith healing, religious authority and beliefs not based on experimentation. He ended up being known as the Father of Botany and was even the tutor of Alexander the Great, which is impressive enough in itself. But for us, his main claim to fame of course is that he was the first to put pen to paper about Arum.

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

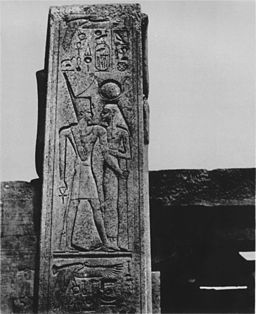

Arum and the Earliest Illustrated Plant Guide

Arum is included in the first ever illustrated plant guide. Made from stone.

Arum is featured what might just be the earliest plant guide ever. Dating from an incredible 3500 years ago and located in Egypt in modern day Luxor, are pictures of two Arum species carved in stone in the temple complex at Karnak. They were created by the ancient Egyptian King Thutmos III.

Thutmos III expanded the areas conquered by ancient Egypt massively and is considered by Egyptian historians to have been a military genius. He also seems to have been a keen gardner as well. He brought back from his 'conquerings’ an ever growing collection of new and unusual of plants. Presumably keen to enthuse his fellow Egyptians with a love of botany and green-fingeredness, he ordered that carvings of these exotic new plants be created on the walls of the temple in the appropriately named 'Court of Flowers'. Though the garden which accompanied this temple, and in which many of these plants were grown, has never been found, the carvings are still there. They were partly to show off just what a great plant collector he was but also to show people what these new plants were. A kind of early 'spotters guide' I think.

They represent the earliest known illustration of Arum. and interestingly, two distinct species are depicted, which shows an attention to botanical details which was to appear only fleetingly over the next few thousand years.

Arum was considered important enough to carve into the temple walls because it was probably already an important food plant. This would likely be a variety of the tropical Arum usually known as Taro. It has large, starch rich roots which are a great source of carbohydrates. Just perfect for eating and completely unlike the roots of the European Arum we have here, which are small, deeply buried and filled with flesh-burning crystals. We'll look at this again when we get to the the role the European Arum has played as a food stuff.

So this is where our timeline of Arum begins. In ancient Egypt with the first guide to plants, as a picture book carved in stone 3500 years ago. Isn't Arum just amazing?

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad

Read more on the iPad book here: http://tinyurl.com/wildarumipad